Development of Next-Generation

Background and need for research

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are increasing at an accelerating rate (NOAA, USA), casting doubt on the viability of the human race. According to the IEA's roadmap published in 2021, global CO2 emissions should have been slowing down by 2025 and reduced to around 30 billion tons per year (p. 152 of the roadmap), but in reality, it has been reported that the global emissions have exceeded the 40 billion ton (40 gigatons) mark in 2023 (Energy Institute, UK, 2024). It has been scientifically proven that the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration contributes to global warming (Syukuro Manabe, Nobel Prize in Physics 2021) and that the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration is primarily anthropogenic (IPCC AR6 WG1, Chapters 1 & 3; see also the website of the Royal Society). In fact, the global temperature has been steadily increasing (Copernicus, EU), and in particular from 2023 to 2024, it clearly exceeded the previous global average temperature and set a new record high (Copernicus, EU).

The recent climate changes are causing natural disasters (UNEP), hungers (WFP), and health problems (WHO) on a global scale. From a different perspective, some researchers pointed out fundamental problems with humans as a species, such as the concern that humans may not be able to maintain concentration (and hence intellectual activities may be hindered) if CO2 concentrations exceed 1000 ppm (Satish et al., 2012). In this way, the problem of rising atmospheric concentrations of CO2 not only jeopardizes the future survival of humanity but also poses an imminent danger to our current lives and the order and well-being of our society.

When considering solutions to this problem, the most important perspective is the "quantity perspective." As mentioned above, humans currently emit approximately 40 billion tons of CO2 annually. Japan emits about 1 billion tons annually (Ministry of the Environment of Japan, April 2022). In particular, Japan's top 10 emission sources emit more than 10 million tons at a single location (Kiko Network, 2017, in Japanese).

In recent years, research on 'carbon capture and utilization (CCU)' has become active. While CCU has a certain significance as a way to respond to economic and social requirements to reduce emissions through carbon pricing or an ESG viewpoint, the following three perspectives are considered important. (1) Is the amount of its reuse meaningful compared to the CO2 emissions of the above order? (2) How does the CO2 used for reuse come to be separated? (3) Energy input is required for CO2 separation and reactions such as CO2 reduction (and in some cases, the generation of hydrogen to be reacted with CO2), but are these energies available? In other words, if the context is to solve the climate change problem, a quantitative and systematic perspective is needed.

A representative technology for a quantitative solution is the geological sequestration of CO2, known as 'carbon capture and storage (CCS),' which is already in large-scale operation around the world (Global CCS Institute). However, the more we envision the capture of CO2 from large-scale emission sources, the more we are faced with the question of how to do it and whether the energy and equipment costs for capture are realistic. The current technology is the aqueous amine solution method described next; however, this has problems, and therefore, research is needed to solve the problems.

Problems with existing technology and points that require improvement

The current technology is a chemical absorption method that uses an aqueous solution of amine molecules (e.g., primary amines are -NH2), in which CO2 molecules react with the amine molecules in the solution and are captured (Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 2022). When the CO2 is desorbed (or the solution is regenerated), thermal energy must be applied to break the chemical bonds formed between the CO2 and the amine molecules. However, the primary problem with the current technology is that it is also necessary to heat the solvent water, which makes up most of the weight of the liquid (sensible heat), and to input the additional large amount of thermal energy to turn the water into vapor (latent heat). Although improvements in absorbent solutions are currently being made (COURSE50, in Japanese), they are mainly based on efforts to reduce the heat of reaction between amine molecules and CO2 molecules, not on reducing the sensible and latent heat of water as a solvent. There is a limit to the approach of lowering the heat of reaction, because the reaction rate and heat of reaction are inversely related (COURSE50, in Japanese). Therefore, lowering the heat of reaction too much will result in an economically unacceptable equipment size due to the need to increase the contact time between the amine solution and flue gas, since liquid is generally a slow diffusion medium for gas molecules.

In addition, aqueous solutions of amines are highly corrosive to metals and harmful to the ecosystem and human health (Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 2022), which increases, respectively, the cost for frequent maintenance inspections of equipment and replacement of amine solutions and the cost for scrubber facilities to prevent the release of solute amine molecules into the environment. In other words, if we are aiming to lower the heat of reaction, dramatically reduce the energy input required in the regeneration process, and solve environmental problems, we need to stop using aqueous solutions.

Therefore, the necessary improvements are (1) to avoid using water, which causes excess heat capacity (sensible & latent heat) and low gas diffusion coefficient, i.e., to make it solid, (2) to ensure high reaction rate by using porous solids rather than tight solids, and (3) not to use support materials that can cause excess heat capacity and weight. Among them, (2) is necessary to avoid the above-mentioned dilemma that reaction rate and reaction heat are in a trade-off relationship. If gas diffusion and reaction are faster in porous media, the heat of reaction, which is a part of the energy input required in the regeneration process, can be reduced without side effects.

Idea and aim

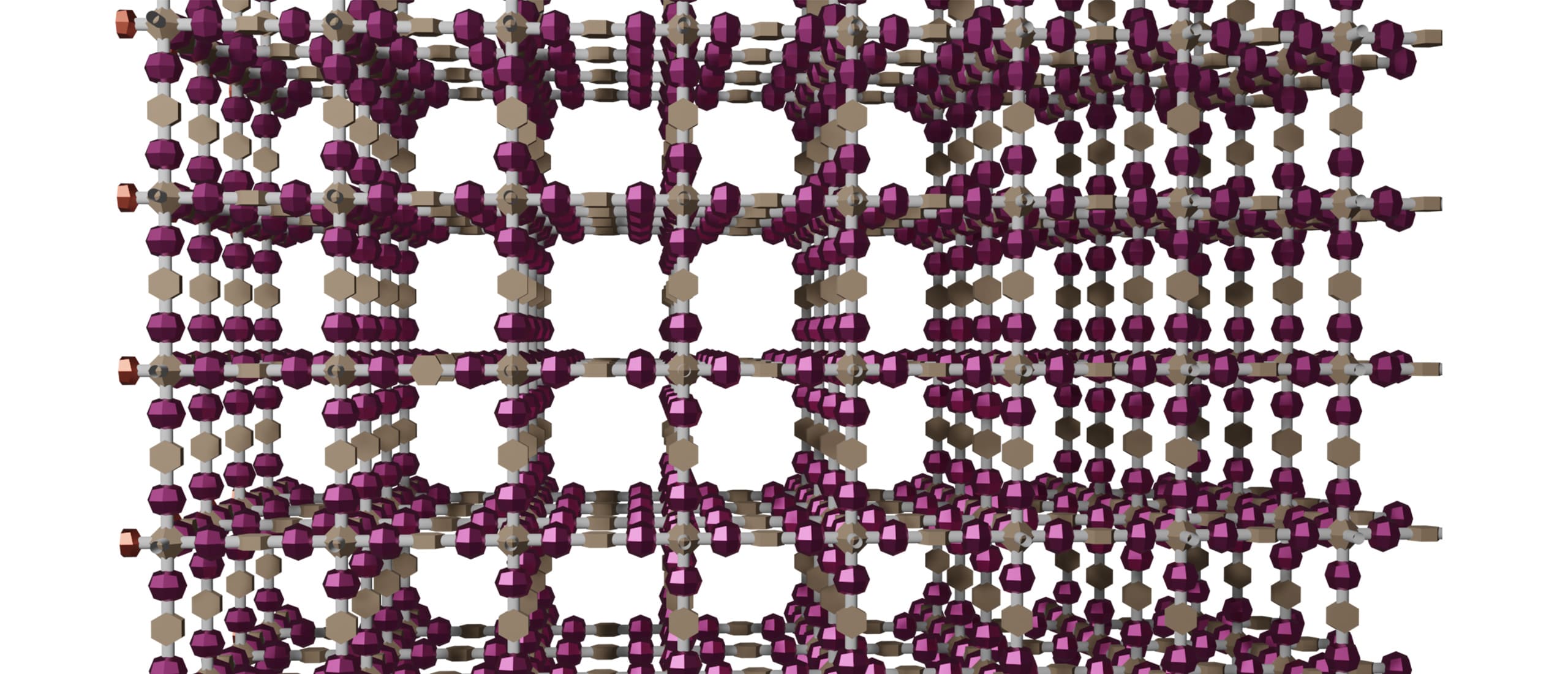

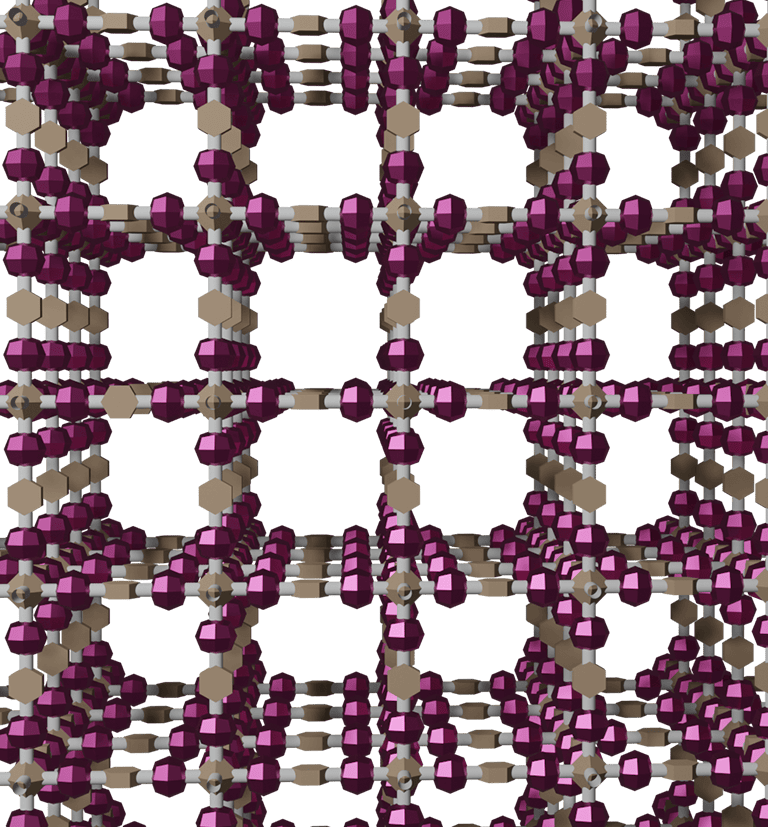

The idea of this research is to use "covalent organic frameworks (COFs)" explained below, as a porous material that can effectively solve the above-mentioned problems. COFs are crystalline organic porous materials that have attracted much attention recently because they are composed only of light elements (usually C, H, O, and N), metal-free, highly durable because they are constructed with covalent bonds, and have nanoscale pores that are sufficiently larger than CO2 molecules. COFs are, to say, "jungle gyms" consisting of molecular rods, and their pore size and function can be designed by selecting building block molecules. We believe that using COF, specifically if amine adsorption sites can be densely arranged on the COF's skeleton, we can create the ultimate solid CO2 absorbents that are solvent-free, support-free, porous, highly stable, and consist of only light elements.

Because COFs are organic solids, they must be kept below 200°C for long-term use in the presence of oxygen. This is a much lower temperature than the temperatures used in the methods that use tight-lattice inorganic materials; this is because the gas diffusion coefficient (or mass transfer coefficient) of tight-lattice inorganic materials is small, and hence such inorganic materials require the use of high temperatures to ensure the reaction rate.

Furthermore, the use of relatively low temperatures has principled advantages based on thermodynamics. Simply put, the act of separating gases to lift off the mixing state at a high temperature will, in principle, require higher energy input for the gas separation, because a high temperature favors disorder or the state with increased entropy. If one wants to reduce the energy input for CO2 separation, separation and recovery should be performed at as low temperatures as possible, which is rooted in the fundamental principles of science. (Note: There is a limit because too low temperatures slow down the rate of molecular diffusion and desorption within the material, but if there is a "porous material with low heat of adsorption," that will be avoided. If a tight-solid or liquid is used, however, the mass transfer coefficient will be lowered, so higher temperatures are needed to ensure the reaction rate.)

We are conducting such research from the development of COFs to the system-level performance evaluations, to create an innovative CO2 capture and separation technology that can be deployed on a large scale to mitigate climate change. We recently published a paper reporting a new class of COFs with excellent CO2 capture properties. We are currently aiming to achieve even higher performance and lower costs to realize industrialization.

Related news release: "New 2.5-dimensional skeletons in porous organic crystals are key to superior CO2 separation," EurekAlert! (AAAS)