Development of Next-Generation

Background and need for research

The rapid increase in variable renewable energy sources due to the recent spread of solar and wind power generation has led to frequent output curtailment (disconnecting renewable energy sources from the grid because they cannot be consumed by the demand side), which was previously unthinkable. This has not only led to the waste of renewable energy but also caused large price fluctuations in the electricity trading market. In the United States, Europe, and Australia, the expansion of renewable energy has even led to negative electricity market prices (i.e., people paying a fee to have the electricity they generate taken away). An effective solution to this problem is to store electricity at the generation site using secondary batteries and adjust supply and demand by shifting it over time.

Furthermore, in recent years, there has been a trend toward the electrification of vehicles and other mobile objects, with the aim of reducing CO2 emissions, promoting the use of renewable energy, and combating environmental pollution in residential areas. Drones are also a type of mobile object. For such purposes, secondary batteries are essentially required to be lightweight and have a high energy density to maximize driving range, and to be highly stable against various external disturbances to maximize safety.

However, most current secondary batteries use organic solvents as electrolytes, which increases the risk of fire. This is because organic solvents generally have a boiling point of around 80 to 200 °C, vaporize easily, and become flammable gases when mixed with air. For this reason, serious fire accidents have occasionally occurred in portable electronic devices (Forbes, 2023), power storage facilities (MIT Technology Review, 2025; PV Magazine, 2023), automobiles (EV FireSafe; MIT Technology Review, 2025), and aircraft (2013 Boeing 787 Dreamliner grounding, Wikipedia).

One promising solution to this problem is all-solid-state secondary batteries, which eliminate the boiling point, vapor pressure, and the possibility of forming flammable gases, by solidifying the electrolyte. This technology field is the subject of intense R&D competition. However, as described below, even current all-solid-state batteries have problems. The one background to the problems is that most R&D efforts to date have been focused on 'inorganic' systems, where material exploration is limited to the scope of the periodic table, while limited R&D efforts have been made on 'organic systems,' which have virtually infinite design freedom. We believe that using less-explored organic materials, when combined with the ideas described below, will be effective in solving the problems of current inorganic all-solid-state batteries and achieving lightweight and high-performance. This is why research on this topic is necessary.

Problems with existing technology and points that require improvement

The materials currently used for the solid electrolytes of all-solid-state secondary batteries (especially all-solid-state lithium-ion secondary batteries) are inorganic, and can be roughly classified into 'sulfide-based' and 'oxide-based' materials (Adv. Energy Mater., 2021). The common problem is that the electrolyte is an inorganic solid with a low degree of deformation freedom. As the active material repeatedly expands and contracts during charging and discharging, the interfaces between the electrolyte, electrodes, and active material (which should be in close contact) tend to peel off, resulting in a loss of contact between them (Chem. Rev., 2020). Because sulfide-based materials are softer than oxide-based materials, interfacial delamination can be reduced by applying pressure to restrain the expansion of the cell; however, the use of such a constraining container leads to an increase in the battery weight as well as the cost.

Currently, the types of batteries being considered for use in vehicles, which require large capacity, are sulfide-based solid electrolytes, which are relatively flexible (compared to oxide-based ones) and have high ionic conductivity. Japan is leading the way in this technology field. For example, Idemitsu Kosan and Toyota Motor Corporation are collaborating to achieve mass production (News release from Toyota, 2023). This sulfide-based solid electrolyte is made from sulfur components generated during the manufacturing process of petroleum products, and has the potential for large-scale production. Because it is sulfide-based, it is said to be crack-resistant (Toyota Times, 2023). However, sulfide-based solid electrolytes have the drawback of generating highly toxic hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas when they come into contact with moisture in the air, even at very low moisture concentrations (ACS Appl. Energy Mater., 2024). Additionally, strict dehumidification control is required during the manufacturing process, which significantly increases manufacturing cost (example: descriptions in the webpage of atomfair.com).

Oxide-based solid electrolytes, which can avoid this drawback, have been put to practical use in small, low-capacity batteries. However, they generally have low ionic conductivity around room temperature, and the material particles are hard and brittle, so they need a hot-press sintering at high temperature for several hours (Small, 2023). In addition, their brittleness makes them poorly compliant with volume expansion and contraction. Furthermore, some applications, such as drones, require not only safety but also light weight, making it important to reduce the weight of the restraining container used to prevent the aforementioned interfacial peeling.

One way to achieve significant improvement would be to soften the solid electrolyte so that it could follow the volume change of the electrode active material, but inorganic materials are usually hard and brittle; this is the root of the difficulty. The flexibility issue could be resolved by switching to organic materials such as polymers and plastics. However, existing solid-state lithium polymer batteries have a drawback in that the dense polymer electrolyte has low ionic conductivity, resulting in a generally low transference number (the fraction of current carried by lithium ions in the total current; in inorganic electrolytes, it is often close to 1).

Idea and aim

To solve the above-mentioned problems, this research aims to develop a new solid electrolyte that satisfies the following three points: (1) It is an organic material that is flexible and allows for a high degree of freedom in material design. (2) The material is not dense, but rather a crystalline porous material that can achieve high ion conductivity (at least with micropores larger than the conducting ions). (3) The material can conduct only positive and negative ions (i.e., single-ion conductive) and hence achieve a transference number of 1.

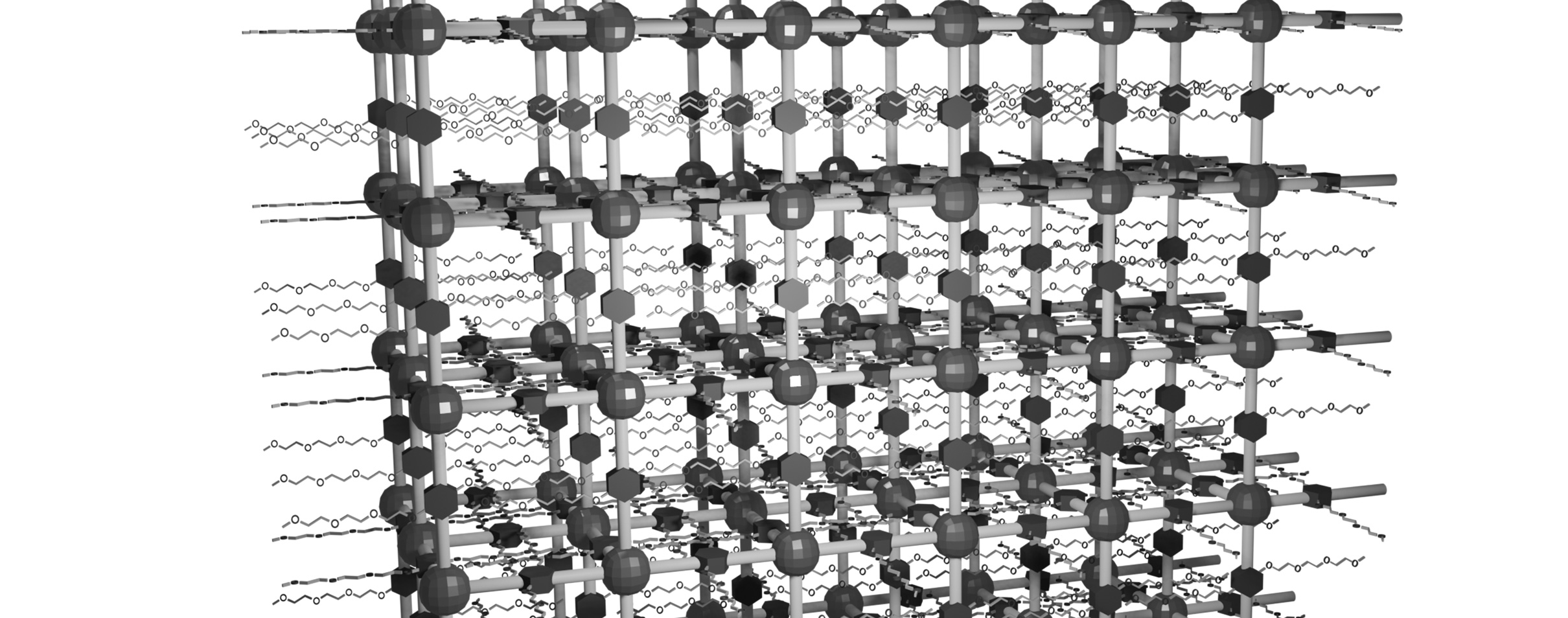

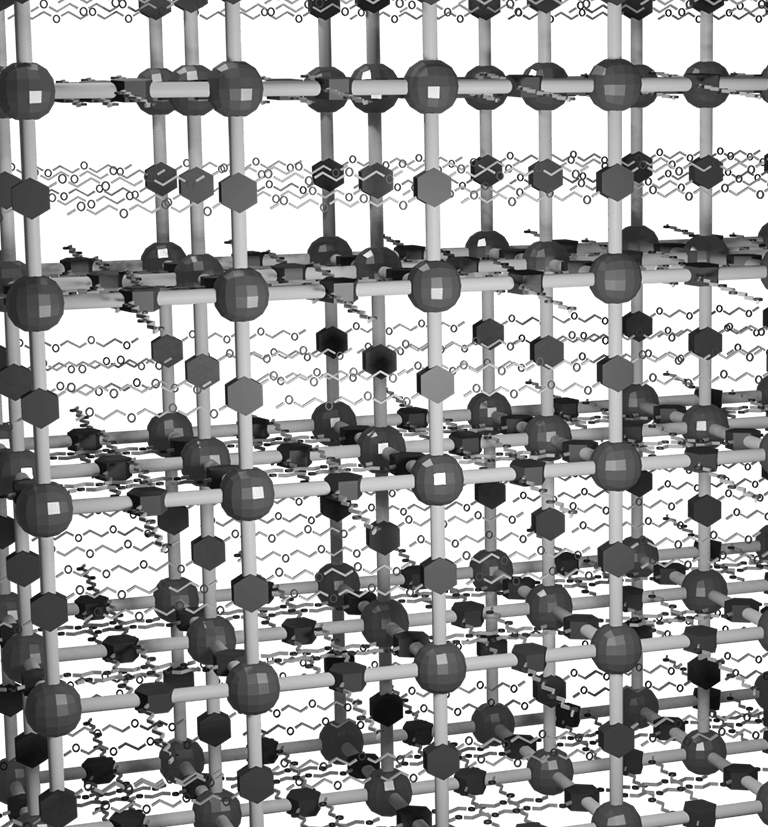

As a material system that can satisfy these requirements, we have chosen "covalent organic frameworks (COFs)" explained below. COFs are crystalline porous polymers and are a class of materials that have been attracting attention in recent years, because their structure and properties can be designed with a high degree of freedom. The above condition (3) can be achieved by using building block molecules that ionize the framework, thereby imparting selectivity to the COF for ions of the opposite charge. Although the synthesis of such COFs has been reported in several previous studies, their crystallinity was significantly low, and they appeared amorphous even when viewed under a scanning electron microscope (example 1: page 22 of SI of ACS Energy Lett, 2020; example 2: page 8 of SI of Nano Lett, 2021). Low crystallinity poses the following obstacles to achieving the above-mentioned objective (application as an electrolyte in solid-state batteries). The channels or pores of a COF with single-ion conductivity can be compared to a highway. However, if the highway ended every 100 meters with a toll booth, followed by a short, slow-speed road, followed by another 100-meter section of highway, and so on, the benefits of the highway would not be fully utilized. Each section of highway would need to be at least tens of kilometers long. In this analogy, the length of the highway section corresponds to the grain size of the individual COF crystallites that make up the material. Increasing crystallinity increases the grain size, which allows ions to transport more smoothly, i.e., improves ionic conductivity.

The reason for the low crystallinity in previous research is that COFs are constructed using highly stable (high binding energy) covalent bonds (in the field of COFs, this is called the crystallization problem). On the other hand, through our efforts to date, we have accumulated know-how for producing COFs with high crystallinity. In particular, we believe that our technology for generating highly crystalline COFs and for structural analysis is at a very high level. Furthermore, the COF skeleton can often deform like a pantograph, making it highly adaptable to large deformations (example: page 27 of SI of our paper, JACS, 2024). Furthermore, low-density COFs (less than about 0.5 g/cm3) can also have the mechanical flexibility of a sponge (example: page 27 of SI of our paper, JACS, 2025).

COFs that satisfy the above (1) to (3) should be possible by selecting the building block molecules properly. However, the reason this has not yet been achieved is that COFs have not yet been produced with high crystallinity. We believe that if COFs with crystal sizes of around tens of microns can be produced, it will be possible to form the "highway with a section tens of kilometers long" mentioned above. Furthermore, as a more challenging attempt, we are creating membranes of COFs. If this is achieved well, it is expected to become a game-changing, innovative material that will solve the problems of the current inorganic-based electrolytes.

(Note: The COFs need to be resistant to oxidation and reduction to prevent themselves from decomposing, and this may be achieved by increasing the oxidation state and reduction state of the COFs, respectively. One of the features of COFs is that, because they are porous, the entire framework can be oxidized or reduced by post-treatment after COF formation.)